|

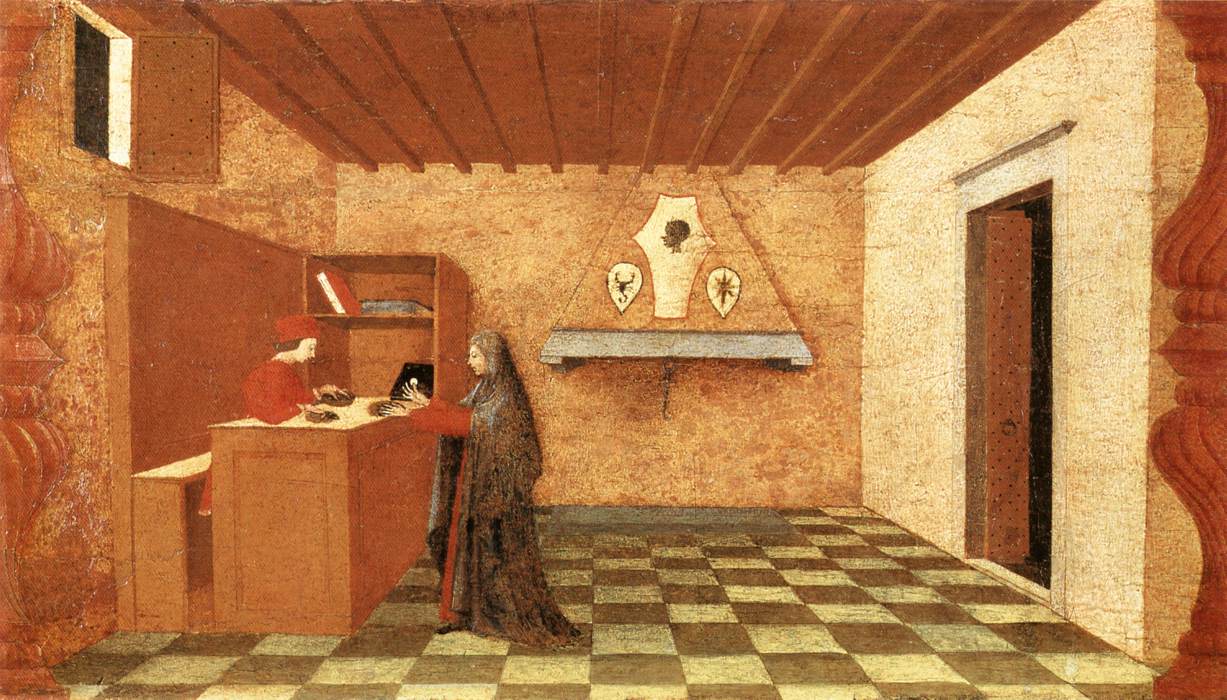

| Raphael, School of Athens, 1511 (detail of Alexander the Great) |

This could be either one of two people: Alcibiades or Alexander the Great.

Although I don’t have any schools of thought to ramble about, I do have strategic geniuses who were actually pretty stupid in their free time. While history may try to glorify these two, let me assure you that I will expose them for the dudebros they are.

Alcibiades was basically anything but a philosopher. First, he worked for his native home of Athens, but evidently decided that Sparta looked so much cooler (that and he was charged with sacrilege). While in Sparta, he worked against his former ally of Athens, but he eventually made more powerful enemies in Sparta, and was forced to leave. He defected to Persia where he was the adviser for the satrap until his enemies demanded a recall. Yet, when he returned to Athens, he did not fall from power. On the contrary, Alcibiades became an Athenian General until (surprise, surprise) his enemies had him exiled. All in all, Alcibiades war tactician for not one, not two, but three different empires.

On the other hand, Alexander the Great spent his formative years in a pissing contest with his father that lasted for years after his death. For a brief time,

|

| Bust of Aclibiades as every Greek man |

Alcibiades was basically anything but a philosopher. First, he worked for his native home of Athens, but evidently decided that Sparta looked so much cooler (that and he was charged with sacrilege). While in Sparta, he worked against his former ally of Athens, but he eventually made more powerful enemies in Sparta, and was forced to leave. He defected to Persia where he was the adviser for the satrap until his enemies demanded a recall. Yet, when he returned to Athens, he did not fall from power. On the contrary, Alcibiades became an Athenian General until (surprise, surprise) his enemies had him exiled. All in all, Alcibiades war tactician for not one, not two, but three different empires.

On the other hand, Alexander the Great spent his formative years in a pissing contest with his father that lasted for years after his death. For a brief time,

Alexander was tutored by Aristotle beginning at the age of thirteen. In return, Alexander’s father Philip II, restored Aristotle's hometown, which he had formerly razed.

What leads me to believe that Raphael stuck Alexander in there rather than Alcibiades was that, while Alexander may have been more jock than nerd, his contribution and intellectual legacy lives on through Alexandria. After Alexander founded the city, it became a wealth of knowledge. Of course, this didn't last for very long. It was soon destroyed by the growing Christian presence in the city.

At any rate, maybe Raphael should have just painted the city of Alexandria in there, but I digress.

|

| Super Alex: short, ginger, and angsty |

At any rate, maybe Raphael should have just painted the city of Alexandria in there, but I digress.