Henri Matisse painted a great number of pieces centralizing on the form of the human body. In this series, painted between 1907 and 1910, his figures can most commonly be found capering, playing, and making music. These works, at the time, were considered uncomplicated in both composition and color. Yet, Matisse’s work with the human form left an indelible impact on his successors.

“What I dream of is an art of balance, of purity and serenity devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter - a soothing, calming influence on the mind.” – Henri Matisse

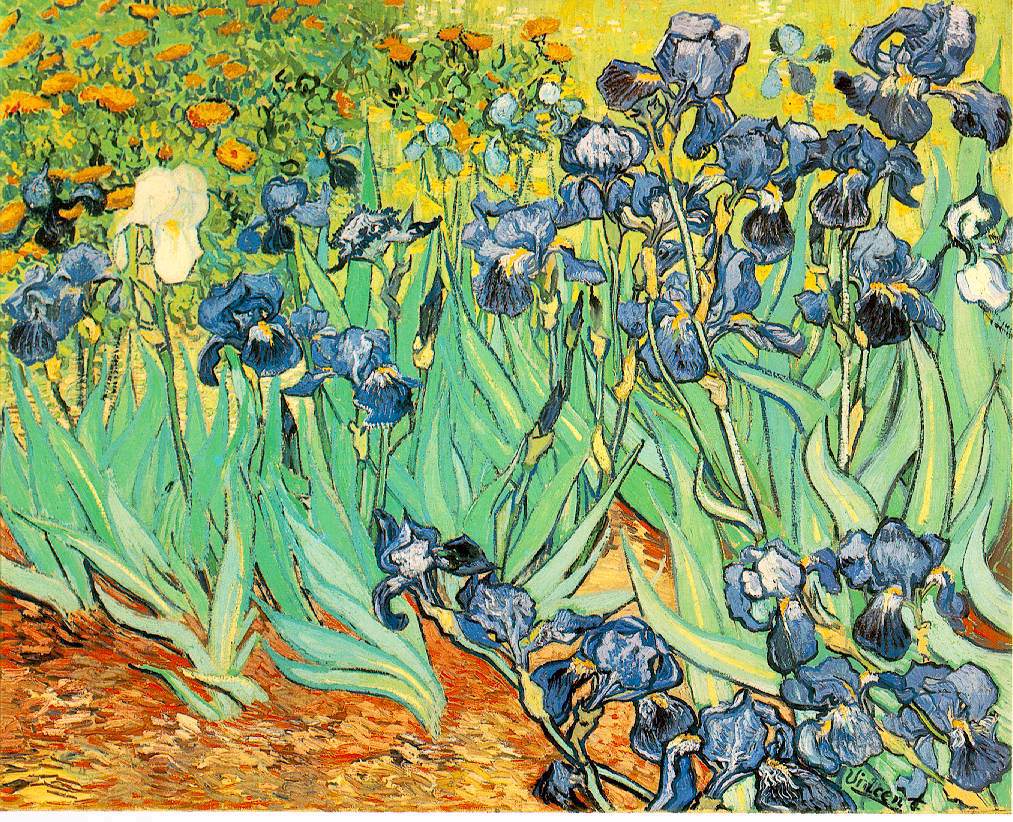

William Carlos Williams’ 1923 poem Spring and All parallels Music in an unconventional way. Now, one could relate a poem like Langston Hughes’ Life is Fine to Music, through highlighting the metaphorical rise and fall of Hughes’ narrator with Matisse’s oscillating subjects. Yet, Williams’ poem of awakening and self-awareness more closely parallels what Matisse accomplished in Music. Williams’ prose forms a gradual crescendo of activity; from a wintery, cold, and desolate setting, to a livelier and less ominous one. Music’s subjects mimic this crescendo perfectly, moreover they parallel Williams’ object in their battle against the ground.

Spring and All

By the road to the contagious hospital

under the surge of the blue

mottled clouds driven from the

northeast -- a cold wind. Beyond, the

waste of broad, muddy fields

brown with dried weeds, standing and fallen

patches of standing water

the scattering of tall trees

All along the road the reddish

purplish, forked, upstanding, twiggy

stuff of bushes and small trees

with dead, brown leaves under them

leafless vines --

Lifeless in appearance, sluggish

dazed spring approaches --

They enter the new world naked,

cold, uncertain of all

save that they enter. All about them

the cold, familiar wind --

Now the grass, tomorrow

the stiff curl of wildcarrot leaf

One by one objects are defined --

It quickens: clarity, outline of leaf

But now the stark dignity of

entrance -- Still, the profound change

has come upon them: rooted they

grip down and begin to awaken

under the surge of the blue

mottled clouds driven from the

northeast -- a cold wind. Beyond, the

waste of broad, muddy fields

brown with dried weeds, standing and fallen

patches of standing water

the scattering of tall trees

All along the road the reddish

purplish, forked, upstanding, twiggy

stuff of bushes and small trees

with dead, brown leaves under them

leafless vines --

Lifeless in appearance, sluggish

dazed spring approaches --

They enter the new world naked,

cold, uncertain of all

save that they enter. All about them

the cold, familiar wind --

Now the grass, tomorrow

the stiff curl of wildcarrot leaf

One by one objects are defined --

It quickens: clarity, outline of leaf

But now the stark dignity of

entrance -- Still, the profound change

has come upon them: rooted they

grip down and begin to awaken

.jpg)