After the papacy of Innocent X, Pope Alexander VII found himself needing a larger Jesuit Church due to increasing number of officials and attendants. The talented Gian Lorenzo Bernini accepted the offer to create the Sant'Andrea al Quirinale by no surprise. Firstly, Bernini had a relationship with the Society of Jesus, the sponsoring Jesuit group behind the new church, and Alexander. Also, Alexander asked Camillo Pamphilli, a patron of the Church, to fund this project. Pamphilli strongly disliked Borromini, Bernini's main competitor. After Bernini reluctantly accepted the position to lead this project, he made sure he would receive no compensation. He wanted to turn this project from a monetary necessity to a privilege. This would serve as a personal triumph representing his devotion to Christianity. Throughout the years, Bernini became increasingly more invested in his faith. So, constructing the Sant'Andrea for free showed everyone his prioritization of religion over commissions.

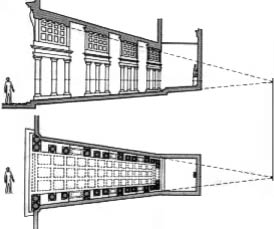

The building itself sits on Quirinal hill on top of the remains of the previous church that Bernini had demolished. The smaller, intimate space has a Palladian facade fronting the oval shaped body. This layout mocks Bernini's rival Borromini's ellipse church down the road from the Sant'Andrea, The visitor upon entering will see the main altar surrounded by red columns and red marbled walls. The somber blue and grey floor is plastered with designs and texts. The oval shape allows the focus point at the end to be the altar. Guillaume Courtois' beautiful Martyrdom of Saint Andrew hangs on the blue wall with a hidden window beaming light from above. The four pillars encasing a statue of Saint Andrew ascending on a cloud represent the Jesuit beliefs. The major component of the church is the fluorescent ceiling lit golden by the yellow stained glass in the center and surrounding. The pattern eerily resembles the honey comb interior introduced by Borromini earlier in San Carlo, his small church that seems to provide the basis for Bernini's designs in the Sant'Andrea. Bernini successfully created a church that pleased both himself and Alexander, however, in the process he managed to undermine the work done by his competitor Borromini years before.

The building itself sits on Quirinal hill on top of the remains of the previous church that Bernini had demolished. The smaller, intimate space has a Palladian facade fronting the oval shaped body. This layout mocks Bernini's rival Borromini's ellipse church down the road from the Sant'Andrea, The visitor upon entering will see the main altar surrounded by red columns and red marbled walls. The somber blue and grey floor is plastered with designs and texts. The oval shape allows the focus point at the end to be the altar. Guillaume Courtois' beautiful Martyrdom of Saint Andrew hangs on the blue wall with a hidden window beaming light from above. The four pillars encasing a statue of Saint Andrew ascending on a cloud represent the Jesuit beliefs. The major component of the church is the fluorescent ceiling lit golden by the yellow stained glass in the center and surrounding. The pattern eerily resembles the honey comb interior introduced by Borromini earlier in San Carlo, his small church that seems to provide the basis for Bernini's designs in the Sant'Andrea. Bernini successfully created a church that pleased both himself and Alexander, however, in the process he managed to undermine the work done by his competitor Borromini years before.

.